Of all the servants in a household such as Calke, the Cook was the one that needed to be kept sweet. ‘Acquiring, accommodating and retaining a decent cook was a constant source of worry.’[1]

A Victorian or Edwardian household totally relied on their cook. No sending out for takeaway’s in those days and no respectable lady would know how to cook. It seems Calke had problems keeping a good cook, especially during the 1850’s where they employed no less than 20 in those ten years.[2]

Regardless of their marital status, they were always called ‘Mrs’ but they were rarely married. The kitchen was their domain, in charge of kitchen maids and scullery maids, ordering all produce and ingredients, liaising with the estate gardeners and suppliers such as butchers and fishmongers, and creating menus.

One of those ‘twenty cooks’ in the 1850’s to work at Calke was Sarah Fogg. She came to Calke in 1855, but she arrived with a bit of a back story. We are lucky to have several letters from Sarah in the Calke Archive and they, along with information from the Census and Church records, tell quite a sorry tale. She was born in Wales in 1815, went into service and ended up working as a Cook at Hovingham Hall near Scarborough. There she met and in 1848, married James Fogg, who was the Butler.[3]

In 1851 Sarah, who had two very young children by then, lived in Scarborough.[4] James, however, was hundreds of miles away in London. It’s not clear what he was doing down there; he may have gone with the family from Hovingham Hall to their London Residence. Charles Palmer, the House Steward at the time at Calke, received a letter in 1855 recommending Sarah for the Cook’s position. Part of the letter states,

‘has previously lived with Sir William Worsley, Hovingham Hall, Yorkshire where she married the Butler and having lost her husband she wishes to go into service again.’[5]

The interesting thing here is that James was very much alive and well. Sarah was hinting that James had died to ‘save face’, but what had really happened was that James had left her with two young children so she had no alternative but to look for work. She was interviewed on February 18th and the very next day (before she had been informed whether the position was hers or not) wrote a letter to Mr Palmer, basically saying that she has accepted a temporary appointment for 2-3 weeks, and begs to have the opportunity of serving at Calke, if they would wait for her.

The next part of the letter gives us evidence that servants had to provide their own uniform. She points out that this temporary engagement will ‘‘furnish me with the means of obtaining suitable apparel for a Gentleman’s establishment without making the sacrifice I otherwise must have done, that is to have disposed of some articles of household furniture which I have left and which I have a great desire to retain for my dear children’s advantage.’[6]

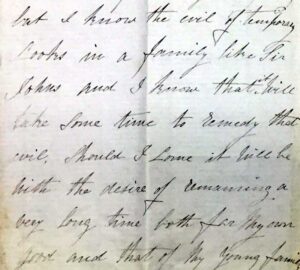

Sarah had also been made aware of the succession of short term cooks that Calke had had to deal with, saying in another letter

‘I know the evil of temporary Cooks in a family like Sir Johns and I know it will take some time to remedy that evil. Should I come it will be with the desire of remaining a very long time both for my own good and that of my young family.’[7]

She was obviously taken on as she appears in the 1855 servants wage lists. There followed 2 letters to Charles Palmer in 1855; one from Sarah asking for a month’s advanced wages because ‘I received a letter this morning from the person that has the care of my children requesting me to lend them some money.’[8] And a letter from S.Bull, who was the head of a servants agency in Derby, saying that when Sarah was coming to Calke Abbey she borrowed 12/6[9] ( 2/6 of that money was ‘for her place’. Going through an Agency was not free, you had to pay if they found you a position) and asks to be paid when she receives her wages.

I don’t believe she stayed more than a few months simply because we have evidence of other cooks immediately after then. But it is not the last we have heard of Sarah because in 1859 she was writing again to Charles Palmer this time asking for a recommendation.

‘I have been living with my husband ever since I left Calke but have decided upon going to service again to enable us to go into some kind of business. I have a situation in view and a recommendation from you would, I am sure, ensure it for me………… I wish I had been in the same state of mind as I am now, I might have been there yet, but the trouble that ???? my mind was almost more than I could bear, I am happy to say that my husband and I are quite reconciled to each other and live on the most comfortable terms.’[10]

I very much doubt the latter statement – but we cannot prove one way or another. We don’t know if the recommendation was sent or not but it is probable that Sarah never went into service again. She died on 14th May 1860 in Halifax, aged only 45, and her occupation at that time was ‘Bobbin Winder’.[11] James was still down in London (which is one reason why I think her statement in her last letter was a lie) and in 1861 he married Isabelle Thompson.[12]

The vast majority of cooks at Calke have been women. I have only found evidence of 6 male cooks, 5 of whom were in the 18th Century. Edmund Grogan was the exception. He was engaged as a ‘Professed Cook’. This was someone who was highly skilled and trained and could produce dishes of the highest quality, for example, foreign dishes and elaborate confectionery. We have a couple of letters from him in the Archive where it is obvious he has been asked to come and cook for a special occasion in 1852. Unfortunately, we have no idea what that occasion might have been. His first letter is obviously in answer to an enquiry about hiring his services. He ‘lets slip’ that he is just about to go to Worsley Hale during the stay of the Queen. (this checks out as correct) and sets out his fees. His second letter in March 1852 asks more specific questions about ‘the number of parties each day’ and whether he needs to procure things in London to bring with him.[13]

We get a little more detail in the Stewards account book for 1853 such as payment for 6 days cooking £5.5s and bills for Preserves, spices and sauces £2.10s 9d and most staggering of all an ‘account for the turtle £5.9s.6d’, which was more than the cost of his wages.[14] That must have been some party!

[1] Life Below Stairs – Sian Evans.

[2] Servants lists Calke Archive DRO

[3] England and Wales birth, marriage and death indexes – ancestry.co.uk 2018

[4] 1851 Census Scarborough Yorks – ancestry.co.uk 2018

[5] Calke Archive DRO 2018

[6] Calke Archive DRO 2018

[7] Calke Archive DRO 2018

[8] Calke Archive DRO 2018

[9] Calke Archive DRO 2018

[10] Calke Archive DRO 2018

[11] England and Wales birth, marriage and death indexes – ancestry.co.uk 2018

[12] England and Wales birth, marriage and death indexes – ancestry.co.uk 2018

[13] Calke Archive DRO

[14] Stewards account book 1853 Calke Archive DRO 2020

Next article, The Ladies Maid