Why is it that we are so interested in the lives of servants? Quite a high percentage of visitors to Calke Abbey have a polite and passing interest in the Harpur Crewe’s, but what they really want to know about is the servants. How many there were. What their jobs entailed and how they were treated. I think it is because so many of us can relate more easily to a person who has had to work hard for a living, rather than one of privilege, who lived a life of luxury.

I have been researching the servants at Calke for about four years now and it has been a real journey of discovery, uncovering stories of joy and sadness, tragedy and success. I hope to share some of these with you in the coming months, but first let’s look at how the whole servant thing worked.

The size of the house, in part, dictated how many servants were employed. Calke, in the nineteenth century, had an average of thirty indoor servants (those that worked in the house including the head gardener, coachman and groom.) Of course, the more money that was available, the more servants you could afford. On top of these ‘indoor’ servants, there would be about eleven gardeners, about ten full-time gamekeepers, stableyard workers and estate workers. All the staff and the financial running of the house and estate was organised by the House Steward, usually an educated man with experience in keeping accounts, although Charles Palmer, who was Steward at Calke for over 40 years, was first employed as a Gamekeeper in 1831 and then was made Bailiff and Steward in 1839. He would deal with all the hiring and firing of the servants.

A question that always intrigued me was how servants got their jobs. We are very lucky at Calke that the family are famous for not throwing anything away. Being a hoarder is generally thought of to be a bad thing, but I, for one, am very glad that the Harpur Crewe’s had that particular character trait because it means that in the Archive at Derbyshire Record Office I have been able to search through hundreds of servant’s letters of application and character references, even for servants that I have yet to find actually got the job.

The most important thing to getting a job was the character reference. Without one it would be almost impossible to get a ‘place’. Young boys or girls getting their first job would most likely apply for a place locally, so that the local vicar, or another such person of standing in the village, could write a character reference for them on their knowledge of them and their family. Once on that ladder though, it would be their employer who would then write the reference if they wanted to move. Surprisingly, servants did move around an awful lot, very often long distances. So how did they find out what jobs were available?

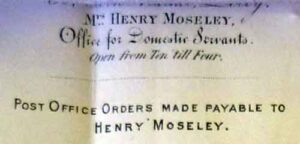

One of the most popular ways was using a Servant Registry. This was an office which matched servants with the people needing servants. These registries were all over the country (there were at least three in Derby) and servants could write to any of them requesting a job. Houses like Calke who needed servants paid a monthly fee to selected offices for their help in obtaining suitable servants from their books. Calke used Ann Moseley’s Servant Registry in Derby and also Samuel Bull’s, also in Derby.

Servants might apply for another job for all sorts of reasons. They just felt like a change, maybe they weren’t happy in their current place, they wanted to move nearer to home, or they wanted promotion. It was rare for a servant to be promoted ‘in-house’, mainly because it could be difficult when given a sudden position of authority over friends and colleagues you had been previously working alongside. So, a servant would write to a Registry Office with details about themselves, their experience and what job they were looking for. This was all free, so many wrote to several registry offices to increase their chances. Meanwhile, establishments like Calke would get in touch when they needed to replace a servant, giving their requirements. Ann Massey, for example, would then match their request with a servant on their books and put the two in touch with one another. If the servant got the job, then he or she would pay the Office two shillings and sixpence.

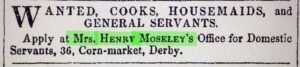

They could, of course, bypass all this and advertise directly in the newspapers (both the servants and the employers). You can find pages of these adverts in nineteenth-century newspapers.

Over the next few months, I shall write about the strict hierarchy in the household and tell some individual stories from Calke including tragedy, the stigma of illegitimacy, tales of romance and other fascinating stories.

Next article Servant Hierarchy.

Leave a Reply